Today’s newsletter includes:

AI Has No Concept of Truth

Review of “Way Station ” by Clifford Simak

Recommendations

Finally…

What you can expect in my newsletters: musings on things I'm thinking about, an occasional short story, links to articles I enjoyed, updates on writing projects, books I recommend, freebies and deals I hear about, news, upcoming events where I'll be, and more.

Newsletters are supposed to go out monthly, usually on Saturday—and maybe that will be true this summer.

AI Has No Concept of Truth

It depends on people to define what is true

What is true?

In the world of coded instructions, something is true if it satisfies the parameters of the query. For example, if you ask, “Is Value-X a number?” it will generate either a ‘true’ or ‘false’ response. That aligns with our thinking and we would reply “yes” or “no”.

The problem shows up when we ask about facts we consider true. AI can tell us whether something shows up in its records or its analysis of those records, but it has no way of judging whether that information is valid or not. “George Washington was the first king of the United States” will show up as “False” if it isn’t found in the data banks—but if that sentence has been added into the files, it will say “True” regardless of whether it has any historical basis.

The ‘truth” AI works with is entirely dependent on what information it is fed. And from what I’ve heard, the Internet has been one of the main sources for training ChatGPT and other AI platforms.

Is that a problem?

Most people function this way to some extent except we have a few key filters we use to reduce the amount of information we have to process. We choose the information we consume based on those filters.

Ideally, we have been taught to analyze what we’re offered and reject nonsense, things which fail to line up at the most basic levels. Even more ideally, we’ve learned how to vet our sources and figure out which ones tend to be reliable. And most ideally, we learn how to research and test information with something of a scientific approach.

Does AI have anything comparable?

How would it go about vetting sources or reproducing conclusions? How would it set up a plan for collecting data and comparing it to the sources it considers trustworthy? Most importantly: How does it define what is trustworthy when figuring out what can be trusted?

In anything, in everything—AI is dependent on people to define truth.

We might be feeling pretty good about ourselves at this point. But unfortunately, the average person puts very little effort into testing information or vetting sources or evaluating ideas and theories critically.

We are more likely to rely on gut feelings and knee-jerk reactions. We gravitate toward entertainers, influencers that stroke our ideas of ourselves, fluff that glosses over facts and soothes our restlessness, our insecurities, our unease about the future.

It isn’t that hard to resist these impulses, to find a variety of sources from differing points of view and compare them. It takes work though. And some of us are tired, or super-stressed, or depressed, or intimidated by the problems of the world.

At least we have the capacity to tackle it.

Artificial Intelligence doesn’t know what is true unless we tell it. It accepts whatever we (or the people feeding it) say. It makes me wonder, who is doing the telling? And what if they use this as a means to deceive? “Ahem…what if?” you may say.

Exactly.

The good news is that deception as a tactic in the world has been around for a long time and the tools are there to resist it. The bad news is, most people aren’t sure how to protect themselves against it. But there are enough people—real human beings—who care about getting the word out and protecting us from being taken advantage of, that it is possible to maneuver these bogs. Like phishing, for example. It’s exploding as a tactic to defraud and rob people and there are many speaking out on how to avoid it or recover from its ravages.

AI has no tactics or tools or inner ear to pick up on clever deception. Maybe one day the coding will be sophisticated enough that we will be impressed with its skills, but it will never be human enough to develop its own sense of discernment.

It will always, always depend on people.

I’m guessing, based on the layman’s knowledge I have of human development, that we develop some of this analytical ability as infants. Babies put things in their mouths and feel the dimensions. They gaze at things with two eyes and reach for them and develop a sense of depth perception. They learn to walk with a lot of falling and train their brain to interpret and communicate all that is needed for balance. Brain development, you could say the physical realm, creates a burgeoning sense of reality. And as they begin to understand language, it builds on that core and develops a basic sense of true and false. Good and bad. Preferred and unwanted.

How do you code for that?

Is there misinformation in the world? Yes. And there is also real information.

Are there deep fake videos and pictures? Yes. And there are also real people doing real things.

Two eyes are enough to determine depth perception. Two locations and a tower are enough to triangulate a signal and find a cell phone. Two different types of sources, (not the same perspectives), are enough to reveal areas that need to be researched and evaluated. I don’t think we are helpless against the vast reaches of AI. We have reasoning skills it will never have.

Let’s stop giving AI more credit than it deserves…although as a sci-fi author with central AI characters in my stories, I do it all the time.

But that’s fiction and I know the difference.

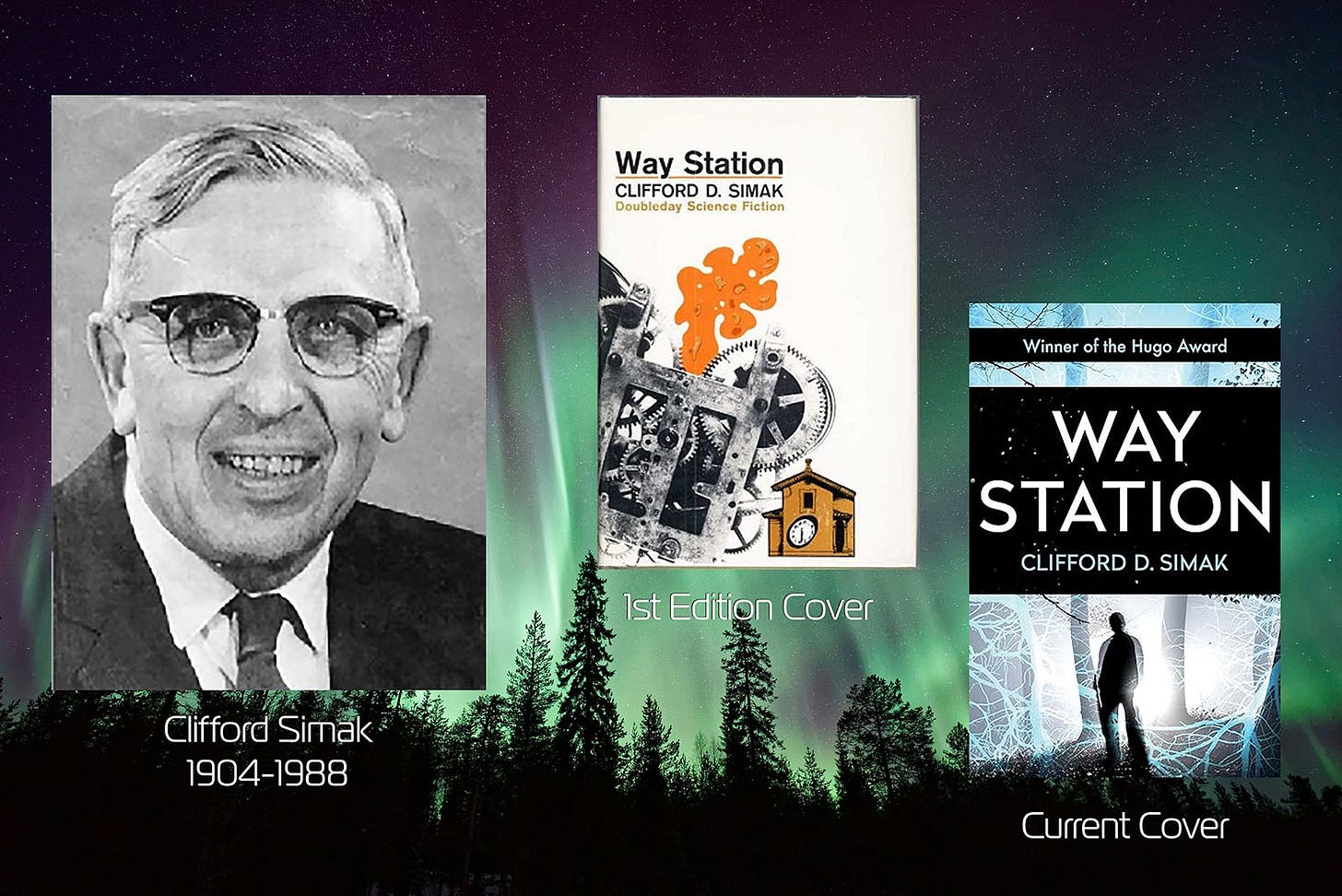

“Way Station”

Simak is one of the classic 20th century sci-fi authors that defined the genre and is worth reading at some point. The books I’ve read bridge the gap between an idealized view of rural or small town American life and the developing future of advanced technology, space travel, and AI.

I decided to review “Way Station” because it’s a Hugo award winner and one of his most well-known.

What it’s about

“Way Station” is about an ordinary 19th-century man who agrees to host a way station for traveling aliens and does so peacefully for decades until a young girl runs into him with disaster in her wake.

My first impression

The farming country backdrop was a little dull for me at first and the only reason I kept reading is because it was easy to fall asleep to at night and he writes well. Simak is one of the well-known, older sci-fi authors that I sometimes feel obliged to spend time with and I just have to adjust my expectations and decide not to mind the setting. Simak philosophizes at times and the ideas come across as dated which is no surprise.

Why I liked it

The plot, interweaving alien concerns with human government surveillance and local community prejudices, is interesting and the main character likable. I appreciated the perspective that there were multiple alien races in the universe that stopped by Earth on their travels and were content with visiting one human. The idea that we humans aren't ready to face gracious aliens is a strong thread in older sci-fi and this book shows how that mindset works. I'd like to think that, generally speaking, people are kinder now to strangers and those who are different from us than the 20th century authors feared, but it isn't so. Our planet is filled with both wars and peace, violence and acts of generosity. We humans are twisted, and at the same time, there are those among us who consistently live for the betterment of the world. Anyway, I enjoyed the book and appreciated how Simak contemplated the mess our world is in.

What I might change

It got boring. I would have preferred to reduce some of the author's philosophizing. I'm not quite as comfortable with the "sitting on the front porch" feel in a fanciful yarn as it's not something I can relate to. I also get a little frustrated with older stories that hint at alien worlds but invest next to nothing in portraying them for us. Simak gave some interesting alien descriptions, but little about their worlds. The whole book takes place in a rural earthly setting.

At times when I was young, I felt a sense of loss and disappointment at this approach. Now, though sci-fi is more likely to have well depicted alien worlds, it sometimes seems as though the authors and artists have been playing the same games, watching the same movies, and there is less originality. There’s nothing wrong with that. If an alien world is familiar, it’s easier to dive into an exciting story without having to paint too much of the backdrop. And readers often appreciate a familiar setting.

Type of read

Slow, thoughtful, something of a mystery set in sci-fi that is more of a commentary on the human race than an adventure.

Recommendations

I am currently reading “The Eon Series” by Greg Bear and really enjoying it. I’m also continuing to enjoy Kristine Katherine Rusch’s books.

Some of my interests in the realm of life sciences that have no direct link to sci-fi include:

Podcast—I love “This Podcast Will Kill You”. A couple of epidemiologists focus on a specific disease or medical condition in each episode covering the biology, the history, and the current outlook for each one.

Great Courses—I recently started watching “Epigenetics” with Dr. Charlotte Mykura, (which I got for a really good sale price), and was spellbound by the vivid portrayal of living DNA and how it works.

Book—This book by Jennifer Vanderbes, “Wonder Drug: The Secret History of Thalidomide in America and Its Hidden Victims“, is powerful reading, beautifully researched and extremely well-written. I found it captivating and sobering.

Finally…

On a personal note, there are many demands in my life; balancing business, family with longterm needs, and personal health with writing means that I am always having to adjust my expectations of what I can accomplish. I have had spurts of time to work on “Eclipse” and am desperate to finish it. There are whole series in my head waiting for this bottleneck to clear—well, it isn’t a bottleneck and my writing isn’t stuck. I just have to keep my priorities straight and people are more important than books.

I don’t regret the time spent caring for loved ones.